BC can’t say how much it collects in luxury car tax, inquiry reveals

(Image courtesy of CBC)

Unlike a lot of other provinces and US states, BC imposes a surtax on luxury vehicles — a so-called “luxury car tax,” but this wasn’t always the case.

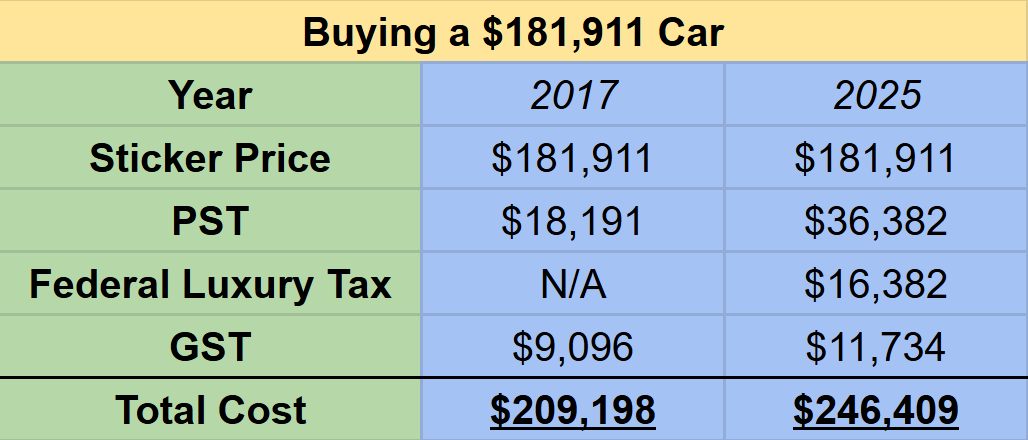

Before the BC NDP’s election win in 2017, BC had a minimal increase in taxes for vehicles. For cars sold for less than $55,000, it was a seven percent tax, going up to 10 percent if a car was sold for $57,000 or above. However, on April 1, 2018, the BC government released a new policy, saying that cars sold at $125,000 — $149,999.99 would be subject to a PST tax of 15 percent, and cars sold at or above $150,000 would be taxed at 20 percent. For instance, say one wants to buy a 2026 Porsche Taycan, which, according to the Porsche website, costs $181,911. Since it's sold above the $150,000 threshold, the total PST levied would be $36,382. If we used the old tax rate, however, it would be $18,191.

Comparison of buying a luxury car in BC today compared to 2017. The federal car luxury tax came into effect in 2022 and is still on the books. The difference between the two years is $37,212 or around 18 percent.

Now, on its face, this does not seem like an unfair and bad policy. The NDP ran a campaign of taxing the very wealthy and making those “pay their fair share,” and is implementing an agenda aimed at that goal. Hard to say British Columbians got duped. Second, it works in theory. They assume that buyers of luxury cars in BC will continue purchasing them at the same rate, and that the new tax will not influence their decisions. It would be very easy to sell to some NDP political strategist who wants to raise tax revenue while also playing hard against the wealthy.

The problem, however, is that rich people, like most people, change their behaviour based on price changes. If a car, particularly a luxury car, becomes more expensive, one is less likely to buy it. It’s basic economics.

Using the Taycan example, for a more fiscally conservative millionaire, the difference between PST rates could change their decision about buying that car, making them either buy a cheaper car or not buy one at all, when maybe if there was a lower tax rate, they might’ve paid.

Try to think of it like this. Say, instead of a 20 percent tax, the NDP implemented a 13 percent luxury tax on all cars sold above $125,000. While the tax is lower, in the aggregate, the BC government could be pulling in more money from luxury car customers, and from a political perspective, collecting more from millionaires, which was likely the main policy goal, right?

Then again, this is all speculation. Maybe the tax does work. Perhaps the BC government sees memos and data that are not publicly available. Coastal Front reached out to the BC Ministry of Finance and asked for this information, breaking down how much the Province received from these taxes at the $125,000 — $149,999.99 and the at or above $150,000 level. A spokesperson for the Ministry of Finance revealed that “[t]he Ministry of Finance receives PST as lump sums from ICBC and motor vehicle dealers. It is not broken down to show the amount of PST that comes from different types of vehicles.”

The province receives PST in lump sums, but without separating revenue from the luxury-vehicle surtax. How can it meaningfully evaluate whether the tax is achieving its goals if it doesn’t even track what it collects from it? What criteria is the government using to assess this policy, if any? And if this lack of oversight extends to other taxes, it raises questions not just about levies aimed at wealthier residents, but about taxes paid by everyday British Columbians as well.

It’s like running a McDonald’s without knowing how many Big Macs, Quarter Pounders, or Junior Chickens were sold. Without that information, you can’t assess what’s working. The broader concern is that the government appears to have no clear performance metric, at least none made public, for evaluating this tax policy. That is troubling, and it casts doubt on the fiscal rigor behind its other tax initiatives as well.