Canada’s quiet hand in Venezuela

Three days into the New Year, the United States ordered a military assault on the capital of Venezuela. The operation resulted in the exfiltration of the country’s president, Nicolás Maduro, and reportedly left 100 dead.

In addition to the capital, Washington also bombed several sites elsewhere in the country. The Venezuelan government denounced the “military aggression.”

“Venezuela rejects, repudiates, and denounces before the international community the extremely serious military aggression perpetrated by the current government of the United States of America against Venezuelan territory and people,” the Venezuelan government said.

Colombia, Cuba, Brazil, Mexico, Chile, and other countries have denounced the US aggression. The response from the Canadian government, and from the general public, was unsurprising.

Careful, good-faith analysis has been drowned out by legions of partisan cheerleaders smugly regurgitating state-crafted talking points or uncritically accepting narratives aligned with their own positions. Ironically, many pundits who have invoked the well-known line about “the first casualty of war being the truth” have proven to be the most emotionally reactive and dogmatic.

Following the flash invasion of Venezuela — coinciding with the anniversary of the 1989 abduction of Panama’s Manuel Noriega and the 2020 killing of Iranian Lieutenant General Qasem Soleimani — theories have proliferated: from claims that Trump operates as a planless troglodyte, lurching from briefing to briefing without coherent strategy; to the view that he is a crude capitalist motivated solely by oil; to more elaborate accounts casting him as an imperial tactician seeking to reassert hemispheric dominance against Chinese encroachment; and, at the outer edge, conspiracies in which Washington and Caracas are covert partners staging a purge of Venezuela’s criminal underworld.

The catalogue of explanations and theories continues to grow. This report does not claim access to the minds of Trump or Maduro, nor does it claim certainty about what comes next. Instead, it confines itself to verifiable facts and measured observation drawn from them. Many Canadians remain unaware that their country has played a role in Washington’s efforts to remove a government long resistant to US policy. What follows is an account of what is known thus far about Washington’s actions and the role Canada has played.

Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, being escorted to a Manhattan courthouse following his abduction by the US.

The indictment

The January 3 superseding indictment released by the US Department of Justice following the military abduction of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro is presented as a legal document, but it reads more like a political brief. The filing accuses Maduro, his wife Cilia Flores, their son, and several political allies of participating in a vast conspiracy to traffic cocaine into the United States. Yet when examined closely, the indictment relies on vague assertions, jurisdictionally tenuous allegations, and the testimony of an incentivized witness whose credibility collapses under minimal scrutiny.

The indictment alleges that Maduro and his associates conspired to traffic “thousands of tons” of cocaine over a period stretching back more than a decade. Elsewhere, prosecutors refer more vaguely to “tons,” without reconciling the discrepancy or explaining how such figures were derived. Beyond citing a broad State Department estimate of cocaine transiting Venezuela annually, the indictment supplies no aggregate totals, sourcing methodology, or corroborating seizure data tied to Maduro himself. It also makes no effort to situate these claims within broader US drug-threat assessments, which in recent years have focused overwhelmingly on synthetic opioids.

Notably, fentanyl — the substance responsible for tens of thousands of overdose deaths annually in the US — is entirely absent from the document, despite the Trump administration's previous assertions that it is engaging in a military campaign in Venezuela to block fentanyl trafficking into the US. Officials have now pivoted on that assertion. The indictment instead relies on a narrative centered on cocaine trafficking at a scale that, if accurate, would imply revenues in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

The document further accuses Maduro of partnering with “narco-terrorist” organizations, including the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua and Mexican cartels. These assertions sit uneasily alongside US intelligence assessments indicating that Maduro did not control Tren de Aragua and reporting that Venezuelan authorities moved against the group in 2023. The indictment does not engage with those findings. Instead, it relies on conclusory language and retroactive designations, including the Trump administration’s 2025 decision to label certain cartels as Foreign Terrorist Organizations years after much of the alleged conduct occurred.

Many of the incidents cited in the indictment are alleged to have occurred entirely outside US territory. One example involves a 2013 shipment of approximately 1.3 tons of cocaine transported from Caracas to Paris. That case was prosecuted in France, resulting in convictions of British citizens with ties to criminal networks in Colombia and Italy. Venezuelan authorities acknowledged corruption among lower-level officials, arrested dozens of individuals, and prosecuted military personnel and civilian airport staff. The indictment nonetheless treats the episode as evidence of Maduro’s culpability, relying primarily on the fact that it occurred months after he assumed the presidency.

Prosecutors also allege that Venezuelan officials facilitated drug movements within Venezuela or between Venezuela and Mexico, asserting US jurisdiction on the basis that the drugs were intended for unlawful importation into the United States. Because most of the alleged conduct occurred outside US territory, that claimed intent is what supposedly allows the case to be brought in a US court at all. Framed this way, the logic is expansive: applied consistently, it could reach the leadership of any country through which drugs flow toward the US market.

The effect is a case built less on demonstrable violations of US law than on a narrative of global criminality in which the United States assumes the role of arbiter, regardless of where the alleged conduct occurred.

Double standards

Further, many of the incidents cited in the indictment are alleged to have occurred in Mexico under the administrations of Vicente Fox, Felipe Calderón, and Enrique Peña Nieto, all close US partners. The indictment’s narrative therefore implicates officials in those governments, including Genaro García Luna, Mexico’s top security official under Fox and Calderón, who was convicted in a US federal court in 2023 for conspiring with the Sinaloa cartel. US officials later acknowledged that they were aware of García Luna’s ties but continued to work with him.

The indictment also points to Honduras under former President Juan Orlando Hernández, describing the country as a transit hub where traffickers paid politicians for protection. Hernández was convicted in a US federal court in 2023 of trafficking more than 400 tons of drugs into the United States, but was pardoned by Trump in December following lobbying by donors tied to the Próspera development off Honduras’s coast. Trump defended the pardon at a January 3 press conference, claiming Hernández had been “persecuted very unfairly.” The case against Hernández was brought by the same DOJ prosecutor who authored the original 2020 indictment of Maduro, Emil Bove.

The star witness

A central source in the indictment is Hugo “El Pollo” Carvajal, a former Venezuelan general and head of military intelligence under President Hugo Chavez. Carvajal is cited repeatedly in support of the most consequential allegations against Maduro, including claims that he had knowledge of, and participated in coordinating, large-scale cocaine shipments, as well as involvement in a purported network known as the Cartel of the Suns (Cartel de los Soles).

Carvajal is presented as an insider with unique access to the inner workings of the Venezuelan state. His cooperation with US authorities followed years of legal pressure, arrest, and exposure to a potential life sentence.

Carvajal was first detained in 2014 on drug-related charges, released, and later indicted again in the United States. In 2017, facing renewed legal exposure, he publicly broke with the Venezuelan government and began presenting himself as a defector. By 2019, he sought asylum in Spain and faced extradition to the US.

After his extradition in 2023, Carvajal pleaded guilty to narco-terrorism and related charges in a US federal court after striking a deal with prosecutors. Reporting confirmed that the agreement leaves open the possibility of cooperation with US law enforcement in exchange for a reduced sentence, contingent on the provision of what prosecutors describe as “substantial assistance” to ongoing investigations. The precise terms of Carvajal’s cooperation remain sealed.

Carvajal’s testimony was delivered under direct incentive: cooperation in exchange for leniency. Carvajal, however, describes his guilty plea as voluntary — an act of accountability undertaken, he writes, so that he could “reveal the full truth so that the United States can protect itself from the dangers witnessed for so many years.”

The Cartel of the Suns… revised

Another element of the indictment that highlights its instability is the Justice Department’s shifting treatment of the so-called Cartel of the Suns. In the original 2020 indictment, the DOJ explicitly accused Maduro of leading a drug trafficking organization bearing that name, referencing it dozens of times and portraying it as a hierarchical criminal enterprise.

By the time of the January 3 superseding indictment, that claim had been abandoned. The revised filing refers to the Cartel of the Suns only twice and no longer treats it as an organization, redefining the term instead as a “patronage system” or “culture of corruption.” The phrase originated as journalistic shorthand in the 1990s. More on that later.

It also raises the question of why a claim treated as established fact for the purposes of sanctions, terrorist designations, and political escalation was later removed right before the case entered the courtroom. Outside the court, the assertion that the Cartel of the Suns was a real organization was treated as justification for sanctions, bombing, covert operations, and the abduction of a foreign head of state and his wife. Inside the court, that same theory was abandoned and replaced with a vaguer description. The result is a clear double standard: an extremely low evidentiary bar for executive action, and a higher one for criminal prosecution.

Even as the DOJ narrowed its language, senior officials continued to publicly describe the Cartel of the Suns as an operational cartel led by Maduro.

CIA involvement in drug trafficking

Another contradiction emerges after the indictment’s core claims are laid out. One that the DOJ’s own history complicates.

The Cartel of the Suns did not first enter the American public consciousness through the Maduro indictment. In the early 1990s, US media reported extensively on a CIA-run operation that involved cooperation with elements of the Venezuelan National Guard to move cocaine shipments through Venezuela and into the United States as part of “intelligence-gathering” efforts. Officers involved wore insignia bearing suns, giving rise to the name later repurposed by prosecutors.

In 1993, a 60 Minutes investigation detailed how US Customs officials intercepted a large cocaine shipment from Venezuela, only to be informed that the operation had been authorized by US intelligence. DEA officials at the time publicly objected, questioning why US taxpayer resources were being used to facilitate drug trafficking into American cities. The reporting made clear that the network prosecutors would later describe as a cartel had its origins not in Venezuelan political leadership, but in US intelligence operations conducted under pro-US governments.

Yes, you read that right.

‘They now call it the Donroe Doctrine’

In announcing the January 3 US military attack on Venezuela and the seizure of President Nicolás Maduro, Donald Trump did not frame the operation as a narrow law-enforcement action. He presented it as doctrine. Invoking the 1823 Monroe Doctrine, Trump declared that “they now call it the Donroe Doctrine,” adding that “American dominance in the Western Hemisphere won’t be questioned again.”

The remark was an explicit assertion of hemispheric authority, issued at the moment of a cross-border military action that killed at least 100 people, according to reports.

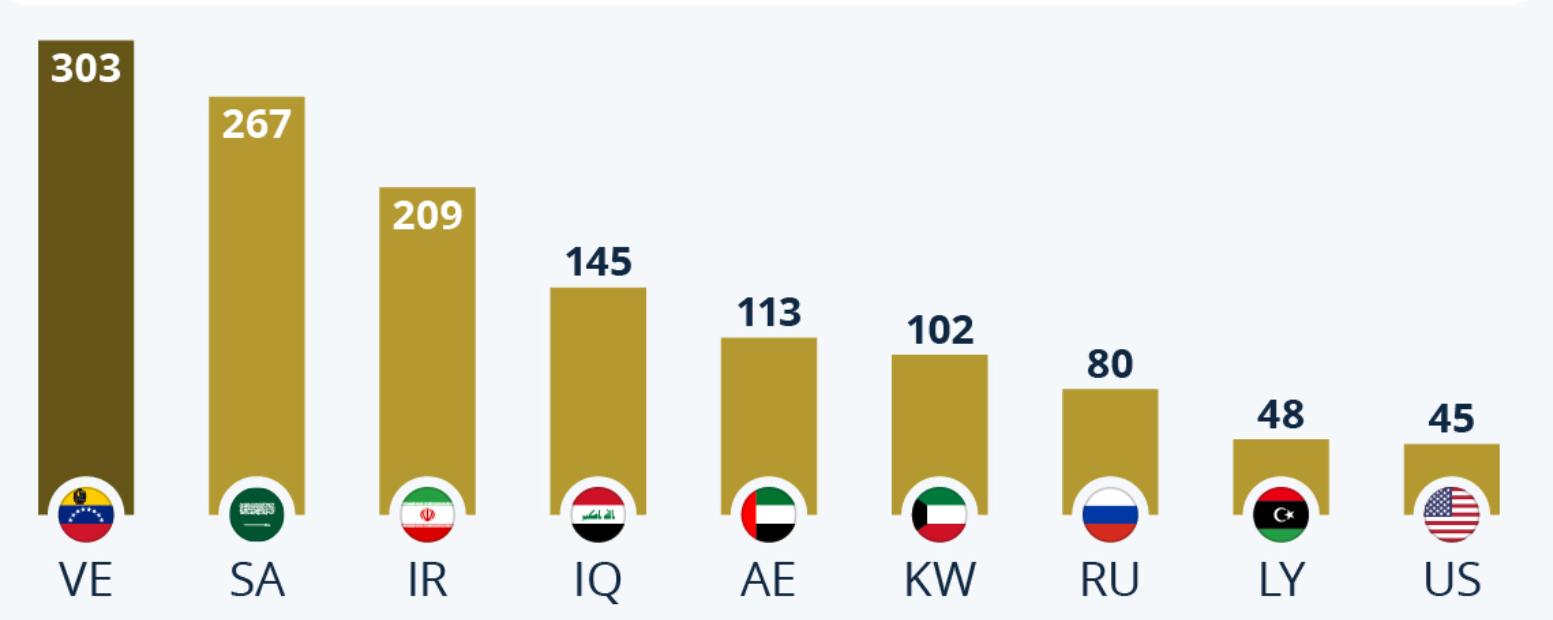

Trump was equally explicit about what that authority would secure. Venezuela, he said, sits atop the world’s largest oil reserves, and under his doctrine, “we’re going to get back our oil… the money coming out of the ground is substantial.” The remarks positioned US oil companies as the main beneficiaries. As Trump described it, the Donroe Doctrine asserted US control in the Western Hemisphere and made clear that this control would be backed by military force.

Countries’ oil reserves. Chart courtesy of Statista.

While Trump portrayed the doctrine as a personal riff on the Monroe Doctrine, it reflected a long continuity in US policy toward Venezuela. For more than two decades, under both Republican and Democratic administrations, Washington has pursued regime change. In April 2002, a rogue military faction briefly kidnapped President Hugo Chávez and installed Pedro Carmona, a businessman with close ties to the Bush administration, who promptly suspended Venezuela’s constitution, legislature, and supreme court. The coup collapsed within 48 hours after mass protests and loyalist military action restored Chávez to power. It did not, however, end US efforts to remove the Venezuelan government.

Venezuela’s open defiance of US hegemony further intensified Washington’s hostility, consistent with earlier US approaches toward governments seen as resistant to American influence. As a State Department memorandum advised in 1960 regarding Cuba, economic pressure was intended to “bring about hunger, desperation and overthrow of government.”

Chávez’s death in 2013 and the subsequent fall in oil prices presented a new opening. In 2015, the Obama administration issued an executive order declaring Venezuela an “unusual and extraordinary threat” to US national security and foreign policy, authorizing targeted sanctions on Venezuelan officials. Under Trump’s first term, pressure escalated sharply. Sanctions targeting Venezuela’s oil sector — responsible for roughly 95 percent of export revenue — were paired with actions affecting key Venezuelan assets, including Citgo Petroleum Corp. in the United States and Venezuelan gold reserves held in the United Kingdom.

Even critics of Maduro acknowledged the impact. Venezuelan economist Francisco Rodríguez described the sanctions as driving a collapse in oil revenues that contributed to the largest peacetime economic contraction in modern history. Former State Department official Thomas Shannon later recalled warning that sanctions would “grind the Venezuelan economy into dust” and produce mass migration, an outcome Trump officials anticipated and, in some cases, welcomed.

As the former US National Security Advisor John Bolton put it, economic collapse and out-migration were “a way to put pressure on the country.”

Trump’s second term did not abandon this trajectory. It intensified it. While Trump envoy Rick Grenell briefly pursued back-channel diplomacy to secure the release of US prisoners, Secretary of State Marco Rubio moved quickly to foreclose any broader rapprochement.

“One of my priorities is to ensure that US foreign policy sends a signal that it’s better to be a friend than an enemy,” Rubio said, branding Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua as “enemies of humanity.”

Rubio’s declaration that Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela are “enemies of humanity” echoes the style of past US foreign-policy labels such as the “Axis of Evil,” a grouping of regimes invoked by the Bush administration to justify expansive interventionist policies.

Under Rubio’s leadership, Washington revived and amplified claims that Maduro was directing a vast narcotics conspiracy and controlling the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua, assertions later undercut by US intelligence assessments concluding that the Venezuelan government probably was not directing the group’s activities.

Nonetheless, the Trump administration ordered military escalation. The US built up forces in the Caribbean, bombed vessels it claimed were transporting drugs, and seized Venezuelan tankers, preventing Venezuelans from benefiting from the oil they are able to produce under crippling sanctions. The UN’s human rights chief condemned the boat strikes, warning that they violate international law and amount to “extrajudicial killing.”

What follows from the “Donroe Doctrine” is not confined to Venezuela, the administration suggested. In public remarks following the operation, Trump and Rubio made clear that the assertion of US dominance in the hemisphere was not limited to that country. Trump warned that Colombian President Gustavo Petro, a critic of the campaign against Venezuela, “does have to watch his ass,” and suggested that “something’s going to have to be done” about Mexico under President Claudia Sheinbaum. Rubio offered his own signal, remarking that if he were part of the Cuban government, he would be “concerned.”

In comments to The New York Times on Thursday, Trump indicated that US control over Venezuela could be open-ended, suggesting it may last for years while offering no timeline or legal justification.

Maduro appeared in a New York court on Monday, where he pleaded not guilty to terrorism and drug-trafficking charges.

Canada’s stance toward Venezuela was years in the making

In the aftermath of Washington’s January 3 military operation in Venezuela, Canadian officials issued their response in familiar language. “Democracy” became the headline: the democratic will of Venezuelans, the illegitimacy of Maduro’s government, moral duty, and so on and so forth.

Canada’s hostility toward Venezuela has been consistent for more than two decades, expressed through support for opposition actors and taxpayer-funded programming that flowed toward initiatives aimed at challenging and ultimately displacing Venezuela’s government.

For example, in 2019, former prime minister Justin Trudeau devoted massive diplomatic energy to Venezuela. Over the course of two weeks, Trudeau raised the issue directly with multiple foreign leaders, including counterparts in Europe, Asia, and the Caribbean. Official readouts from those conversations emphasized support for opposition figure Juan Guaidó and pressure on Nicolás Maduro to relinquish power.

Prime Minister Trudeau with Guaidó in January 2020.

In a call with European Council President Donald Tusk, Trudeau reiterated Canada’s recognition of Guaidó as “interim president.” In discussions with Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez, Venezuela was the sole topic mentioned in the government’s summary. When former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe visited Ottawa days later, the joint statement highlighted Japan’s endorsement of the “Ottawa Declaration for Venezuela,” produced by the Lima Group, which urged support for what it described as the restoration of democracy in Venezuela.

Trudeau extended the campaign to Havana. In May 2019 he contacted Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel to press Cuba to support Canada’s position, emphasizing the Lima Group’s call for free and fair elections and the upholding of Venezuela’s constitution. Days later, then-foreign affairs minister Chrystia Freeland echoed the pressure, publicly stating that Cuba needed to stop being “part of the problem” and become “part of the solution” in Venezuela.

This diplomatic pressure coincided with a volatile moment on the ground. On April 30, 2019, Guaidó, opposition leader Leopoldo López, and others sought to trigger a military uprising in Caracas. The effort did not succeed. Freeland nonetheless reacted swiftly, issuing statements emphasizing the safety of opposition leaders, praising protesters, calling on the Maduro government to step aside, and requesting an emergency meeting of the Lima Group. That evening, the group issued a statement describing the failed uprising as an effort “to restore democracy” and demanded that the military cease acting as an instrument of what it labelled an illegitimate regime.

Days later, Freeland attended an emergency Lima Group meeting in Peru. The resulting announcement accused Maduro’s government of protecting “terrorist groups” in Colombia. At a separate Lima Group meeting in Chile earlier that month, Freeland announced a new round of Canadian sanctions. Forty-three individuals were added to a list of seventy already sanctioned, bringing the total to more than 110.

Public explanations framed the sanctions as responses to repression and judicial misconduct. Venezuela’s government responded by denouncing Canada’s “alliance with war criminals” seeking to collapse the country’s economy and loot its resources. A Center for Economic and Policy Research report authored by Jeffrey Sachs and Mark Weisbrot concluded that approximately 40,000 Venezuelans may have died over two years as a result of US sanctions. The authors argue that the sanctions fit the definition of collective punishment of the civilian population as described in both the Geneva and Hague international conventions, of which the US is a signatory.

In the years that followed Chávez’s temporary detainment in 2002, Canadian diplomatic engagement intersected with opposition activity inside Venezuela. Diplomatic cables later published by WikiLeaks describe Canada’s ambassador questioning the credibility of Venezuela’s electoral institutions and speaking favorably about Súmate, an opposition-linked organization involved in efforts to take down Chávez.

In 2005, then-minister of international cooperation José Verner explained that Canada considered Súmate to be “an experienced NGO with the capability to promote respect for democracy, particularly a free and fair electoral process in Venezuela.” At the time, Súmate was led by María Corina Machado, who had endorsed the 2002 coup and signed the Carmona Decree, which suspended Venezuela’s constitution, dissolved the National Assembly and Supreme Court, and suspended elected officials across multiple levels of government. Machado was invited to Ottawa in January 2005, shortly after her organization led an unsuccessful recall referendum campaign against Chávez.

María Corina Machado. Image courtesy CodePink.

Further, Canada confirmed it had provided funding to Súmate. Parliamentary disclosures show that Canada gave the organization $22,000 that year, with the government justifying the funding as support for democracy promotion.

A 2010 report by the Spanish NGO Fride stated that “Canada is the third most important provider of democracy assistance” to Venezuela after the United States and Spain.

Successive Canadian governments continued this posture. Under Stephen Harper, Ottawa openly opposed congratulating Chávez after his 2006 re-election, joining only the United States in dissent. Harper publicly referred to Venezuela as a “rogue state,” and other officials issued repeated condemnations. After Chávez’s death in 2013, Harper stated that Venezuelans could now build a “better, brighter future,” but when Nicolás Maduro won the subsequent election later that year, Ottawa called for a comprehensive audit of the results and withheld recognition.

By 2017, Canada ramped up its efforts to remove Venezuela’s president. Under Chrystia Freeland’s direction, Ottawa helped create the Lima Group, imposed sanctions, broke diplomatic relations, pursued action at the International Criminal Court, and recognized an opposition figure as president in January 2019.

One day after the US’s January 3, 2026 operation, Prime Minister Mark Carney spoke with the aforementioned Machado, who openly backed the US bombing and blockading her country. Carney’s statement thanked Machado for her "resolute voice," and further underscored, much like his predecessors, the importance of "seizing this opportunity for freedom, democracy, peace, and prosperity in Venezuela."

By the time of Washington’s recent operation, Canada’s position was already well established. Ottawa had spent years aligning diplomatically, financially, and politically with efforts to isolate Venezuela’s government, delegitimize its leadership, and elevate opposition actors. Canadians are increasingly able to see that Carney’s stance was the product of a long, deliberate trajectory — one in which Canada was not a bystander, but an active participant and client state projecting American foreign policy.